Decades ago, after my grandparents had died, I felt called by my ancestors to visit my ancestral homeland and to find my grandparents’ birthplaces. From the years of genealogical research that followed, I know that I am the daughter of Lena, granddaughter of Edvige, great granddaughter of Felicita, and great great granddaughter of Margerita. It is these women in my motherline who beckoned me to retrieve my cultural heritage with a focus on folk women’s culture.

Decades ago, after my grandparents had died, I felt called by my ancestors to visit my ancestral homeland and to find my grandparents’ birthplaces. From the years of genealogical research that followed, I know that I am the daughter of Lena, granddaughter of Edvige, great granddaughter of Felicita, and great great granddaughter of Margerita. It is these women in my motherline who beckoned me to retrieve my cultural heritage with a focus on folk women’s culture.

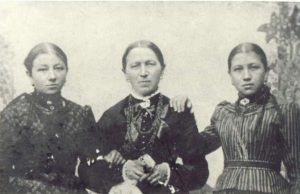

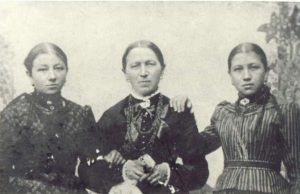

On the eve of February 2, 2007, the midway point on the solar cycle of the year between the longest night and the spring equinox, I opened El Meledri, the periodical from the village of my maternal grandmother in northern Italy, named for the river that borders the village. Inside, there was a photo of three women: my great grandmother, at the center, and her two oldest daughters, Emma and Erminia on either side. Their eyes seemed to look straight across the ages into mine and say, “We’ve been waiting for you.”

Knowledge of my culture was not handed down to me explicitly, as it was for centuries from mother to daughter, parent to child, for a number of reasons including early deaths, immigration to the United States, discrimination, and the missing link of stories tied to particular places.

Much of the oral history was lost due to language. My mother could understand her mother’s spoken dialect (a particular variation of Italian), but she responded to her in English. Here in the United States, my grandmother’s language—the very medium of agency through which her culture had been communicated for generations—became a source of shame, due to her inability to speak “good English.” Her oldest daughter, my Aunt Annie, told me that my grandmother brought her along as a translator in shops to conduct transactions. Through language courses, and with time, my grandmother mastered the English necessary to pass the difficult exam for citizenship, which became a source of pride.

Three years before I was born, my grandmother died while sitting in my mother’s kitchen. As a result, I did not hear a single word of my grandmother’s language growing up. Only in 1981, when I traveled with my mother to Italy so that she could see the birth village of her mother, did this hidden language that she held inside for thirty years tumble out.

In this unfolding story of my heritage, I have sought to recover and make more evident the folk wisdom of my ancestors, particularly of my female ancestors. The arrival of the photo of my bisononna by mail on the sacred day of Santa Brigida, also known as Candlemas, while I was deep in coursework for my dissertation on my ancestral heritage, seemed to be an auspicious affirmation of my Ancestor’s desire to be known.

From my studies and travels, I now know – and thus can appreciate more fully – the numerous ways that cultural values have been transmitted to me in everyday family life, including through food, clothing, medicine, religious practices, acts of service, and celebration.

As a tribute to my mother, Lena Moser, who left this world five years ago today at age 90, it feels appropriate to reprint an excerpt of my introduction from She Is Everywhere, Volume 3. It is a testimony to her resilience (she recovered fully from the episode below), the power of stories to sustain us; and the importance of sharing and caring. Blessed be, dearest Mother! Blessed be!

As a tribute to my mother, Lena Moser, who left this world five years ago today at age 90, it feels appropriate to reprint an excerpt of my introduction from She Is Everywhere, Volume 3. It is a testimony to her resilience (she recovered fully from the episode below), the power of stories to sustain us; and the importance of sharing and caring. Blessed be, dearest Mother! Blessed be!

The blackberries are fermenting on the vine, fallen leaves blanket the picnic table, and the slice of sun on my clothesline arrives later each day. With the arrival of fall, the days of being able to hang my laundry outside are growing fewer. Lately I have been pondering my passion for this ritual of outdoor clothes drying. Is it only the sensual pleasure I crave, or something more?

The blackberries are fermenting on the vine, fallen leaves blanket the picnic table, and the slice of sun on my clothesline arrives later each day. With the arrival of fall, the days of being able to hang my laundry outside are growing fewer. Lately I have been pondering my passion for this ritual of outdoor clothes drying. Is it only the sensual pleasure I crave, or something more?