Recently I traveled to Texas to receive the Kore Award from the Association of Women in Mythology for my dissertation in Women’s Spirituality at the California Institute of Integral Studies, “The Everyday Spirituality of Women in the Italian Alps: A Trentino American Woman’s Search for Spiritual Agency, Folk Wisdom, and Ancestral Values.”

Shortly after I had arrived in San Antonio, and met my younger sister and her daughter who were in town, we received word that my Mother was not well. Although Mom had been in precarious health throughout the last year, she had pulled through several times. That night in the hotel room, we hoped for the best. The next morning as I lay in my dream state, I felt someone come and lay beside me in bed, compressing the covers, which I have come to understand as a visitation from my Mother. Then the phone rang with the news that Mom had died peacefully that morning. It was comforting for me to be with my sister and niece, especially since we were away from home. Together, we made it through that long, rainy day.

Later that morning, my other siblings, who were gathered around my Mother’s kitchen table, called the hotel room where I was staying. They passed the phone around to each person, voicing their consensus that I should stay in Texas to attend the conference, give my presentation, and receive the award. There was nothing I could do in the next few days if I flew to Denver, they said. All the arrangements had already been made; the funeral wasn’t until the next week. So, reluctantly, I surrendered to their decision. My heart wanted to be with them. However, I stayed, unsure. . . .

When I entered the room of the Matriarchal Studies Conference the next day, I was greeted visually by Lydia Ruyle’s banners, dozens of colorful multicultural expressions of the Divine Mother. And then, there was Lydia herself, her head encircled in a wreath of flowers. I whispered to her what had happened and she gave me a big hug, her own heart fresh from the loss of her brother last year. I looked around the room at women from so many places, and saw the altar to Our Lady of Guadalupe they had created. I knew then that I could stay. The nurturing energy was palpable. I felt the support of my siblings from afar and my Mother’s peaceful state from within. My grief of the past year, in anticipation of losing her, was transformed into something else.The kindness of the women I met there nurtured me.

On Saturday, the board members of ASWM ceremoniously presented me the Kore Award. Inscribed on the plaque, along with the title of my dissertation, was a small but important detail: an accent mark on my name, Mary Beth Mosèr, indicating that my ancestry is from Trentino, a precious detail of cultural specificity told to me by Carmela Mosèr, one of my interviewees, at her kitchen table in a northern Italian village.

The next day I flew to Denver to attend a communal prayer to the Virgin Mary, known as the Rosary, said the night before the funeral in the Roman Catholic rite over the presence of body of the deceased. The church was somber, draped inside with purple cloth for Lent, which seemed fitting. The next morning, with sun shining, we – Mom’s seven children, and most of her twenty grandchildren and twenty-one great grandchildren –attended her funeral at Our Lady of Fatima Church. It was poignant to see the participation of so many family members: my nephews as pallbearers and altar boys, my teenage nieces doing the readings with such poise, the grandchildren and great grandchildren bringing up the gifts of offering as part of the Mass. It was a day filled with a particular kind of Grace, inexplicably joyful. Although I had been unsure if I could read the eulogy I had hand written, I found myself drawing from a deep current, some ancient and sustaining source of strength. Later, at the cemetery, the young children were respectful, yet curious as the casket was lowered into the earth. . . how deep did it go, they wondered. . . and cautiously left their parent’s embrace to peek over the edge. There was an irrepressible life-energy emanating from them. It felt comforting to witness first-hand the continuity of the life cycle manifest in them.

I am grateful for our work in women’s spirituality and for our community, which allowed me to honor my Mother and my ancestors in this way. I felt held in a larger spiritual vessel, secure and grounded in my own experience of the Mystery. I know there are times of sadness ahead.

Since that time, I have been in Colorado, fulfilling my role as Sacred Custodian of my Mother’s possessions, a strange mix of legal responsibility and emotional remembering. Together with my siblings, we are figuring things out. Mom led a simple life over her nine decades, which has simplified the process of dispersion. Her clothes went to the Samaritan House, a homeless shelter where she used to volunteer her time, one of numerous acts of service throughout her life. Her reading/magnification machine has gone to someone else who suffers from macular degeneration, a condition that causes loss of central vision. The beautiful painting of the Virgin Mary that hung near her chair in the living room (interestingly, known as the Madonna of the Chair, by Raphael) went to the woman who brought my Mom Communion every morning when she did not have enough energy to go to church.

I claimed Mom’s cast iron skillets, which she cooked with her entire adult life, and the hand-made rosary she carried in 1987 to Medjugorje, a Marian apparition site in what was then Yugoslavia. There were other items that I brought home, precious to me because I knew the story of them from conversations with my Mother over the years as well as from my “formal” interviews of her for my dissertation. Going through her things became a daily ritual act of discovery, a remembrance of my childhood and the lives of my siblings, cousins, aunts and uncles; of my father who died three decades ago; and my grandparents, two of whom I knew as a child.

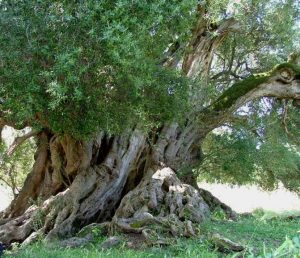

On my first night alone in Mom’s home, with her pearl rosary pressed to my heart, I dreamt about the Black Madonna as a massive dark Tree with breasts – evoking the several thousand-year-old wild olive tree we students saw in Sardegna on a study tour with Lucia Chiavola Birnbaum ten years ago. I awoke with a tingling exhilaration as if I were between worlds.

The journey of my dissertation has been marked with deep sorrow and great joy, great loss and incredible insights, as is also true for so many. It felt strange that this honor of my life-work should be coincident with the end of my Mother’s life. Yet with the timing, she seemed to be saying “Go forward. Your work and your life continue on.”

In honor of Lena Pearl Moser, August 7, 1923 – March 26, 2014 and Lydia Ruyle August 4, 1935 – March 26, 2016

This essay originally appeared on the web site Feminism and Religion.